Government

In response to the Great Depression, President Roosevelt initiated New Deal programs to combat the worst effects of widespread homelessness and hunger. The Public Works Project and, later, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration supported artists who made prints and murals for public buildings.

While the Great Depression began with the stock market crash of 1929, its greatest effects were felt among the masses of American workers. By 1932, one quarter of the workforce was unemployed and, with banks failing, many lost whatever savings they had. Many Americans were at risk of homelessness, hunger and malnutrition. Franklin D. Roosevelt (American, 1882 – 1945), elected to the presidency in 1932, quickly put in place a range of acts and agencies to provide support for the long-suffering people of America, what he called a “new deal” for the “forgotten man.” These included banking regulation and variety of relief programs for workers and farmers. If the New Deal did not in and of itself lift America out of the Great Depression, it managed to protect many from the worst effects of poverty and offered them hope for better times ahead.

Artists, too, were hit hard by the Depression. The private market for paintings, sculptures and the like quickly dried up, eliminating most artists’ means of living almost overnight. In May 1933, artist George Biddle (American, 1885 – 1973)—a childhood friend and classmate of Roosevelt—urged the president to develop a publicly supported arts program as part of the New Deal. The result was the Public Works of Art Project, the first of the New Deal arts programs, established under the Department of the Treasury in December 1933. Although it only lasted until Summer 1934, it supported close to 4,000 artists from around the country and established a precedent that would be continued by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (1935-42), the largest of these programs.

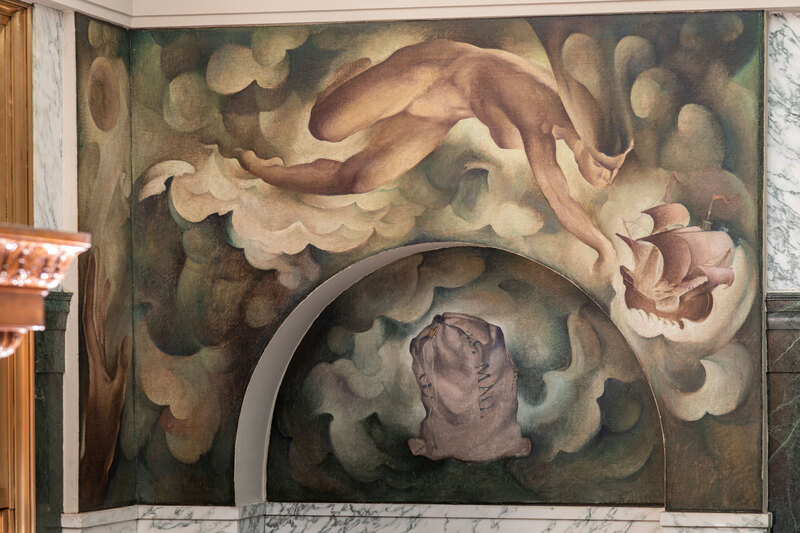

While printmakers working under the aegis of these projects had a fair degree of leeway in choosing subjects and styles, the artists who were commissioned to make murals—artworks destined for the walls of public buildings—were more constrained to work in naturalistic and descriptive modes and to depict what was known as the “American Scene”: aspects of national life and landscape that program administrators understood as embodying “true” national values. Under the Treasury’s Section of Painting and Sculpture (later renamed the Section of Fine Arts, 1934-43) and its Treasury Relief Art Project (1935-38), artists covered the walls of post offices and courthouses with depictions of local history, industry and geography. Some of these murals have been the subject of recent controversy, particularly as contemporary sensibilities around representations of race clash with those of the moment of their creation in the 1930s.

––TMD

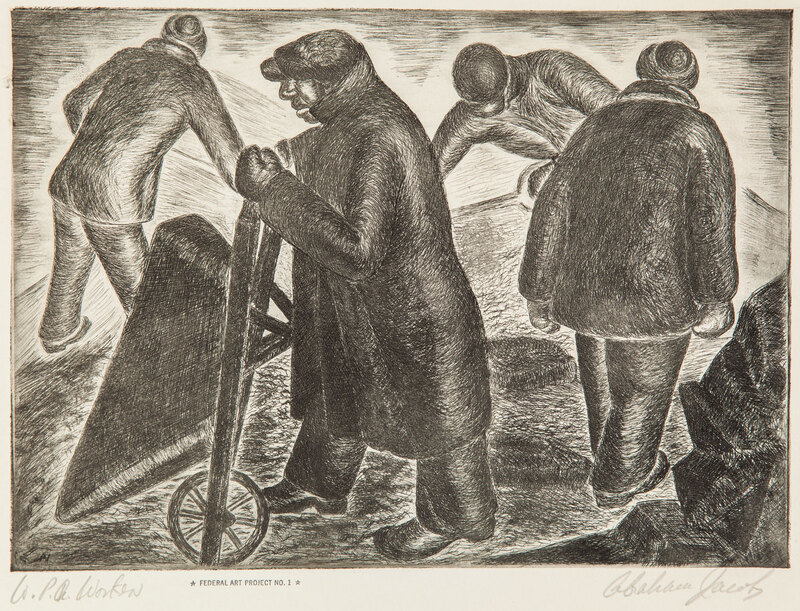

Abraham Jacobs (American, born Poland, 1904 – 1960)

W.P.A. Workers, ca. 1935-43

etching; 10 x 13”

Binghamton University Art Museum, 2016.4.285

gift of Gil and Deborah Williams

Interpretive text has not been prepared for this object.

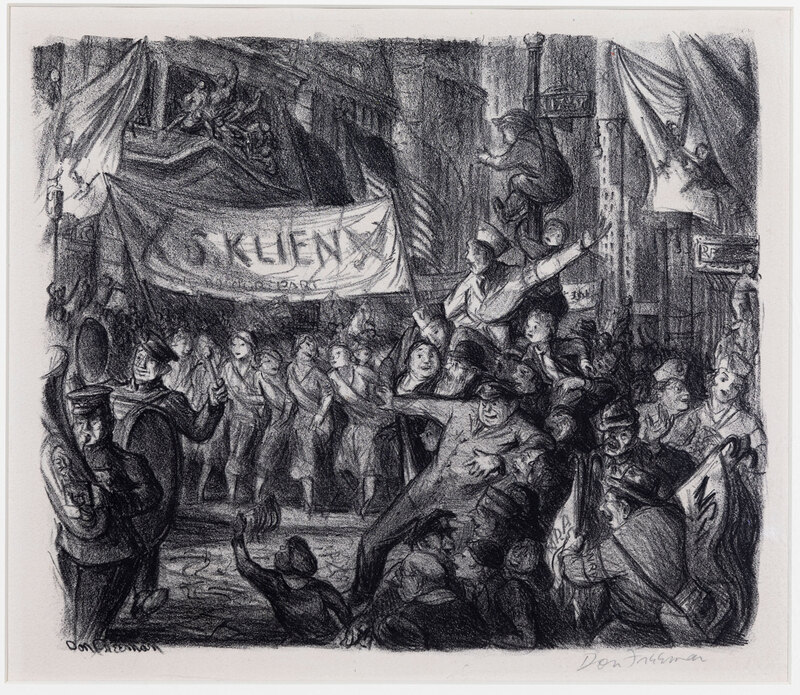

Don Freeman (American, 1894 – 1978)

The NRA Parade, 1934

lithograph; 11 ½ x 15 ¾”

Roberson Museum and Science Center, 1984R46

At the end of Spring 1933, President Roosevelt empowered the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to make voluntary agreements dealing with work hours, pay rates and pricing in order to regulate competition. To drum up public support, the NRA orchestrated a massive public relations campaign, including the largest parade in the history of New York City, held in September 1933.

In Don Freeman’s print, we see a crowd jammed onto the sidewalk as the parade passes the corner of Fifth Avenue and 17th Street. As a marching band exits left, a contingent of shop-girls from the S. Klein department store—located a few blocks south on Union Square—comes into view, carrying a banner emblazoned with the store’s name along with the NRA’s blue eagle logo and its motto, “We do our part.” At the lower right, a man sells NRA pennants to enthusiastic spectators. Made under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project, The NRA Parade is a humorous and sympathetic portrayal of this piece of New Deal propaganda.

––TMD

Austin Mecklem (American, 1894 – 1951)

The 5:28 from Albany on the West Shore at Kingston, NY, 1933

oil on canvas; 24 ¼ x 34”

Roberson Museum and Science Center, 1972M15

extended loan from the United States WPA Art Program. Fine Arts Collection, Public Buildings Service, General Services Administration

Interpretive text has not been prepared for this object.

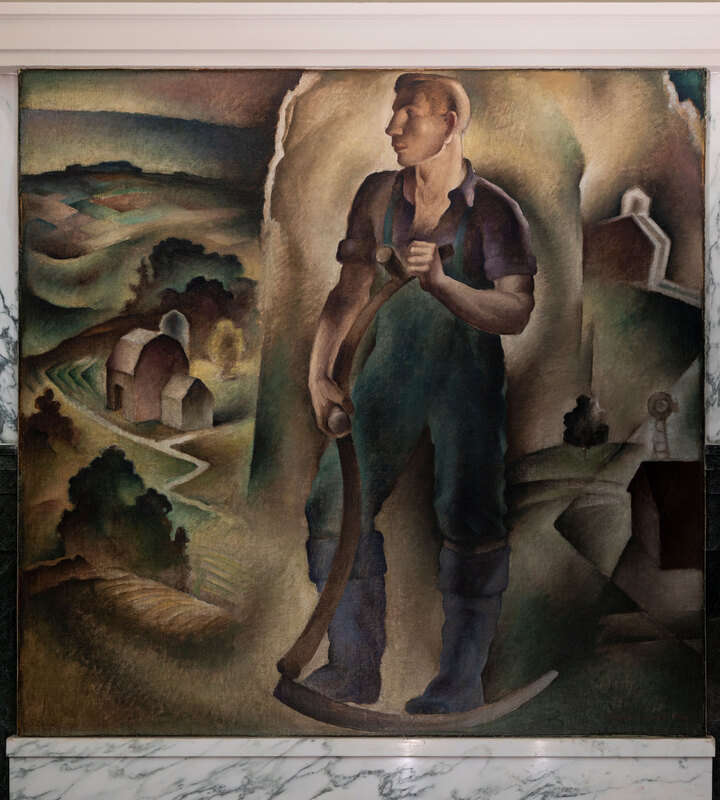

Frederic C. Knight (American, 1898 – 1979)

Air Mail, Shoe Factory Finishing, Train Mail, and Truck and Dairy Farming, 1937

murals, oil on canvas

lobby, Johnson City Post Office

In 1934, a new post office was built on Main Street in Johnson City, a simple red-brick Colonial Revival structure designed by the Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury, Louis A. Simon (American, 1867 – 1958). Three years later, artist Frederic C. Knight was commissioned by the Treasury Relief Art Project—established in 1935 with funds allocated from the Works Progress Administration to decorate federal buildings not funded by the Section of Painting and Sculpture—to produce a group of murals for the walls of its lobby.

Knight, a native of Canaan, NY, turned to increasingly social themes as the Depression advanced in the early 1930s. He then worked under the Public Works of Art Project in 1933-34, and joined the leftwing American Artists’ Congress in 1936. In his Johnson City murals, he combines Modernist stylization in the simplification of human and machine forms and the American Scene topicality in his depiction of, for example, the local shoe industry.

––TMD

Douglass Crockwell (American, 1904 – 1968)

1901 – Excavation for the Ideal Factory, 1938

mural, oil on canvas

lobby, Endicott Post Office

Douglass Crockwell is best remembered for his work illustrating the Saturday Evening Post, one of the most popular American weekly magazines during the first half of the twentieth century, but during the years of the Depression he also created artworks for the Public Works of Art Project and post office murals, including one for the Endicott Post Office on Washington Avenue, a Colonial Revival building designed in 1936 by Walter Whitlack, a consulting architect for the Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury.

Crockwell had initially imagined a mural that would commemorate Endicott’s role in shoe production through an image of columns of marching feet, but Edward Beatty Rowan (American, 1898 – 1946), then head of the Section of Painting and Sculpture at the Treasury, worried that was not likely to be understood by visitors, so the artist turned to this more illustrational vision of the construction of Endicott-Johnson’s Ideal Factory—originally known as the Fine Welt Factory—in the first years of the twentieth century.

––TMD

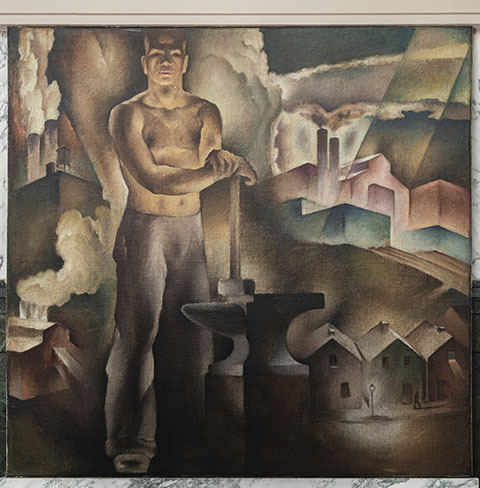

Kenneth Washburn (American, 1904 – 1989)

Modern Worker in Industry & Agriculture, Modern & Ancient Methods of Communication, Communication by Earth, Water, & Air, and Thrift & Postal Savings System, 1938

murals, oil on canvas

lobby, U.S. Post Office and Courthouse (now Federal Building and Courthouse), Binghamton

Interpretive text has not been prepared for this object.

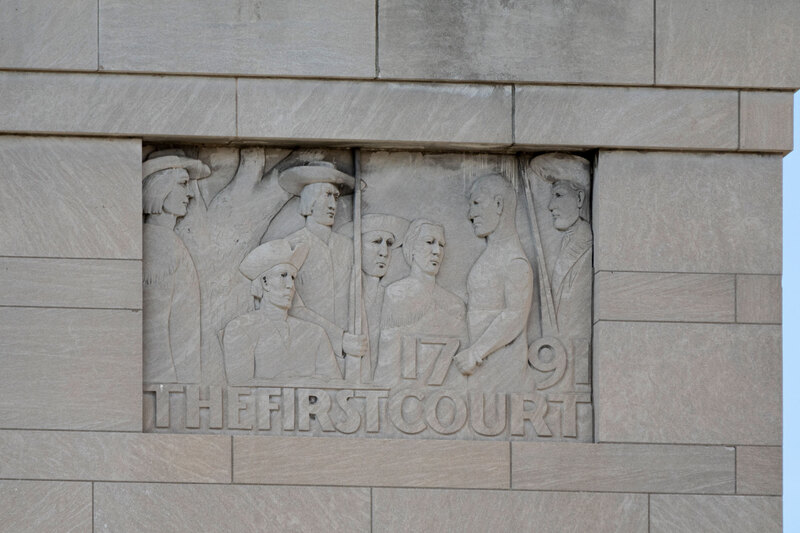

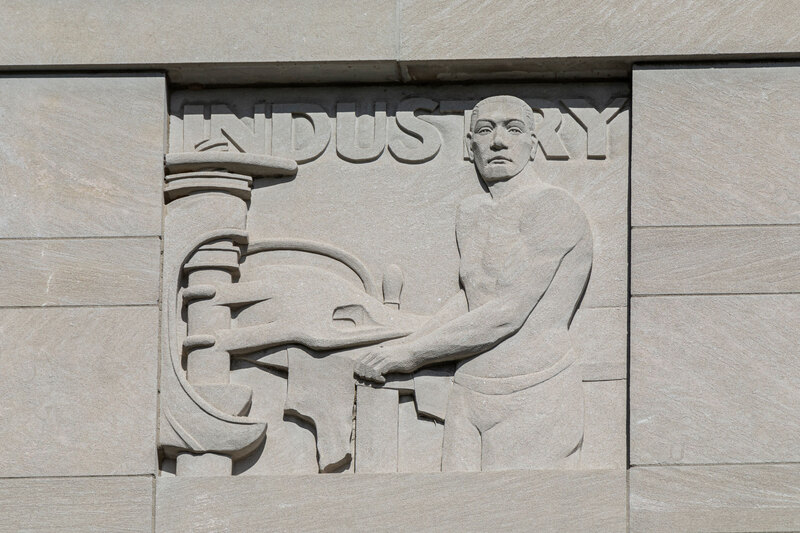

Malcolm Williams

Erie 1848, Law, Liberty, The First Court 1791, Education, Transportation, Chenango Canal, Courthouse 1857, Agriculture, and Industry, 1940

relief panels, marble

façade, Broome County Office Building (now George Harvey Justice Building), Binghamton

Designed by Binghamton architect Walter Whitlock and completed in 1939, the Broome County Office Building originally held offices and a jail and was located directly behind the historic courthouse, built forty years earlier. Its Classical details reference the older building—for example, they both share central two-story porticos with Ionic columns—while its simplified masses and stripped-down forms make it very much an Art Deco building of the 1930s.

Under the wide cornice that runs between the fifth and sixth floors are found ten decorative relief panels that depict significant moments in local history—such as the first court session in Broome County’s history and the operation of the Chenango Canal—and symbolic representations of qualities such as “education” and “transportation.”

––TMD

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904 – 1971)

Washington Monument, Washington, D.C., 1935

gelatin silver print; 6 5/8 x 4 5/8”

Binghamton University Art Museum, 2021.2

Museum purchase with funds from the Binghamton Fund

The iconic Washington Monument, standing on the National Mall in the nation’s capital, was commissioned in the mid-19th century to honor the military and political leadership of George Washington. Dedicated in early 1885, it was celebrated at the time as being the tallest building in the world. Some five decades later, however, its exterior marble cladding had suffered serious deterioration and the National Park Service—which had assumed jurisdiction over the Monument in 1933—undertook its first restoration in 1934, under the auspices of the Depression-era Public Works Administration. To facilitate the work, it was surrounded with tubular steel scaffolding to its full 555’ height.

Margaret Bourke-White, already a respected photojournalist, captures the spectacle of the scaffold-clad Monument in her dramatic photograph of 1935. Photographed vividly from below, it rises in a powerful diagonal from lower left to upper right. The skeletal steel armature transformed the traditional Egyptian obelisk form into an embodiment of modernist engineering, a symbol now not only of America’s past but also of its future.

––TMD